TEMPLER FAMILY

from Somerset, Devon and Dorset

© Andrew Templer 2024

James Templer and the Birth

of British Military Aviation

Michael J Dunn

Originally published Cross & Cockade International -

In 1862, the British Army began to seriously examine the potential use of balloons in modern warfare. Their sudies sought to overcome the shortcomings that had been highlighted during conflicts such as the American Civil War and to turn the balloon into a practical and reliable weapon for use by an army commander. From this small beginning, British military aviation was born. It took over 20 years of hard work for the Army to able to deploy balloons in support of operations; work which was to continue until Britain’s first military airship, ‘Nulli Secundus’, took to the skies in September 1907.

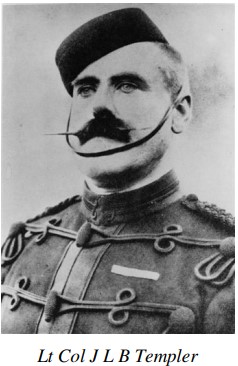

For much of this period, one man, James Lethbridge Brooke Templer, dedicated his life to the development of ballooning for the British Army. For 30 years, he strove continuously to solve a myriad of technical issues and battled against endless political problems, resistance to change, hostility from within the establishment and a constant shortage of funds. He was a man of many talents; a practical man who made things happen. Templer laid out a scientific foundation for ballooning development and took the lead in the task of making balloon units an accepted part of the Army’s establishment. He may arguably be described as the “Father of British military aviation”.

James Lethbridge Brooke Templer

Templer was born on 27 May 1846, the son of John Templer, Master in H. M. Court of Exchequer. He was educated at Harrow and Trinity College, Cambridge. He became a Clerk to the Court of Queen’s Bench and, later a tea broker and an inventor. Templer was an enthusiastic and skilled sports balloonist, the owner of his own balloon ‘Crusader’ and a well-

The pages below explore the evolution of military ballooning within the British Army and focuses on the work of James Templer in establishing air power as an essential, albeit small, force component during peacetime exercises and in war.

The development of British military ballooning may be broken down into 3 phases:

Phase 1 -

Phase 2 -

Phase 3 -

PHASE 1: 1862 – 1878

In 1862, three papers promoting the adoption of military ballooning by the British Army 1 were read at the Royal Engineers School of Military Engineering. They were written independently by Lieutenant G E Grover RE and by Captain F E B Beaumont RE. During the American Civil War, Beaumont was attached to a Balloon Corps, commanded by Thaddeus Lowe, which formed part of the Federal Army under General M’Clellan. The corps comprised 2 ‘aeronauts’, 50 soldiers and 2 balloons. Their tethered balloons provided a constant stream of observation reports throughout the campaign. The value of the information in the reports was dependent on a number of factors that affected the view of the observer: the height at which the balloon was flown, the weather conditions and the distance of the balloon from the front line. In his paper, Beaumont identified problems with the supply of gas, the gas holding capabilities of the balloons and with operating balloons in strong winds. In cautiously advocating the use of balloon reconnaissance by the British Army, Beaumont wrote:

“ …. with a properly constructed apparatus, balloon reconnaissance may be made in a wind at any rate up to 20 miles per hour; the higher the wind the less would of course be the altitude attained: however, a height of even two hundred feet is more than that of the spires of most churches – points of observation eagerly sought for when on the march in an enemy’s country …” 2

Lieutenant Grover’s papers presented a detailed, exhaustive description of the theory of ballooning from a technical and military perspective and touched on the use of balloons in warfare by the Americans and by the French in Italy. Grover wrote:

“It is unsatisfactory to reflect that no definite results have yet appeared from all researches into the question of aerial reconnaissance. Balloons have been advocated by some as most suitable for the purpose; they have been condemned by others on the score of their shortcomings.

Much, therefore, remains yet to be discovered, and though no practical results seem at present likely to be produced in this country from our investigations, yet a consideration on the subject of Reconnoitring Balloons may possibly effect beneficial results eventually.” 3

Captain Beaumont and Captain Grover were duly attached to the War Office Ordnance Select Committee. Balloon reconnaissance experiments up to a height of 1,200 feet were carried out at Aldershot, using a balloon hired from a civilian aeronaut, Henry Coxwell. The results were inconclusive and the already lukewarm official interest largely abated. There was something of a revival following the Franco-

PHASE 2: 1878 – 1899

In 1878, Templer was invited to utilise his balloon experience by working full time for the British Army. He accepted. This act proved to be a catalyst for military ballooning. He agreed to construct a balloon for the Army and the War Office granted £150 for the task. The balloon “Pioneer” and the small hydrogen plant also built by Templer were reported on very favourably by a Select Balloon Committee. They recommended further experimental work should be carried out:

“Captain Templer appears thoroughly conversant with the details of manufacturing and working balloons, and he has carried out the experiments at Woolwich with untiring energy…...The Committee consider that it would be most desirable to retain Captain Templer’s services for the further proposed experiments ……. The Committee consider that Captain Templer should be intrusted with the training of the Officers and men ….”

The recommendations were accepted and experiments carried out, despite the strict limitations imposed on the Balloon Committee’s budget.

In 1879, the Balloon Equipment Store was formed and a year later military balloon training led by Templer and Major H. Elsdale began at Aldershot. A balloon section soonbegan participating in the Aldershot manoeuvres.

In 1881, an event occurred which had great affect on Templer personally and which brought his name to the attention of the general public. He had been participating in a series of meteorological observations using a coal gas filled balloon, “Saladin”. On 10 December, with Templer, Mr. Walter Powell, M.P., and Lt. A Agg-

In 1882, the War Office (WO) ordered that a balloon detachment, commanded by Captain H P Lee and including Captain Templer should be organised for service in Egypt. Equipment to be taken included ‘automatic’ cameras attached to small captive balloons, a portable hydrogen gas plant, telephones and Edison Lamps for night signalling. Manpower was to be provided by 23 Field Company RE. The war ended before the detachment had left and an opportunity to demonstrate the balloon’s potential operational capabilities under ideal conditions was lost.

At the same time, the Balloon Equipment Store and the School of Ballooning (together making up the Balloon Department) transferred from Woolwich to become a sub-

In 1886, a balloon detachment was sent on the first of several visits to the siege artillery practice grounds at Lydd to study the observation of artillery fire from the air, and to try and determine how close to an enemy position a balloon could be worked. The Ordnance Select Committee reported favourably on the observation results but inconclusively reported that the closest safe distance for a balloon was 3,100 yards (the range of the guns). In the same year, Templer leased, at his own expense, some land at Lidsing, Kent. He hired it to the WO for use during the Balloon Department’s summer camps. He dug out a pit so that balloons could be hauled down into it and moored safe from strong winds. Temporary screens were erected to protect balloons at ground level. The Lidsing project was of great value to the Army, and but its overall cost left Templer considerably out of pocket.

An important step forward came in 1887 when the WO accepted a report from Major Elsdale, officer commanding the Balloon Department. With input from Templer, he reported on the current status of British military ballooning. He pointed out the temporary nature of the system by which NCO’s and men were detached for ballooning duties, only to be attached elsewhere ‘faster than we have been able to train them’. He recommended a permanent ballooning unit be established with its own dedicated buildings and training grounds. The WO appointed Major Templer as the permanent Instructor of Ballooning, at a salary of £600 a year. He was also awarded £3,500 towards previous costs such as the lease of Lidsing, his inventions, etc. The Balloon Department’s establishment was increased to:

1 officer in charge

1 instructor of ballooning

Balloon Detachment (Balloon Section)

1 lieutenant

1 sergeant

15 rank and file

Balloon Depot

1 military mechanist

1 civilian gas maker

1 civilian storeman

1 civilian driver

10 balloon-

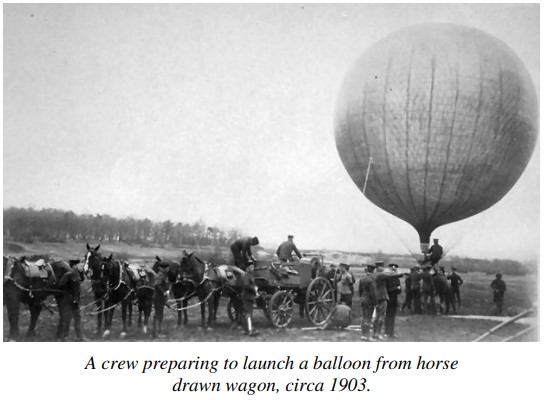

The balloon train (with horses provided by a RE field company) comprised:

1 balloon wagon with hauling down gear

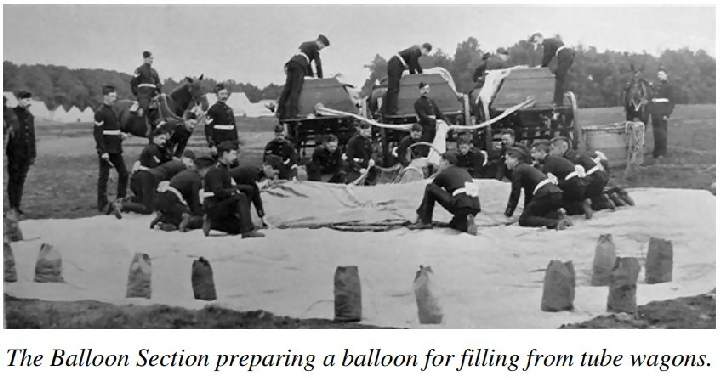

3 tube wagons each carrying 44 tubes

1 equipment wagon with spare balloons and stores

1 water cart

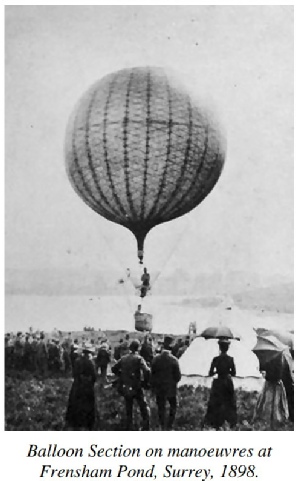

Following the very favourable report from General Sir Evelyn Wood on the Balloon Detachment’s performance at the 1889 Aldershot manoeuvres, a permanent Balloon Section (replacing the Balloon Detachment), comprising 3 officers, 3 sergeants and 26 rank and file, was authorised as an independent unit of the RE.. Shortly afterwards, the Balloon Section and Depot (increasingly now called the Balloon Factory) moved to Aldershot. St Mary’s Barracks Chatham were cramped and unsuitable, training space was limited and the prevailing wind blew directly to the North Sea, thus making free runs risky for trainee balloonists. The WO granted £9,000 for the building of a proper factory next to RE lines at South Camp, Aldershot.

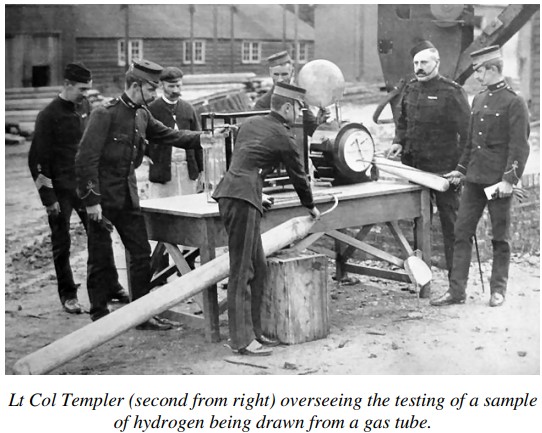

In 1897, command of the balloon establishment was split. Templer was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and appointed Superintendent of the Balloon Factory, reporting to the Inspector General of Fortifications in the WO. Training became the responsibility of the Balloon Section. This operational unit was placed under command of the GOC of Aldershot Army Corps. The split between the operational and manufacturing sides of ballooning remained until after the formation of the Air Battalion RE in 1911.

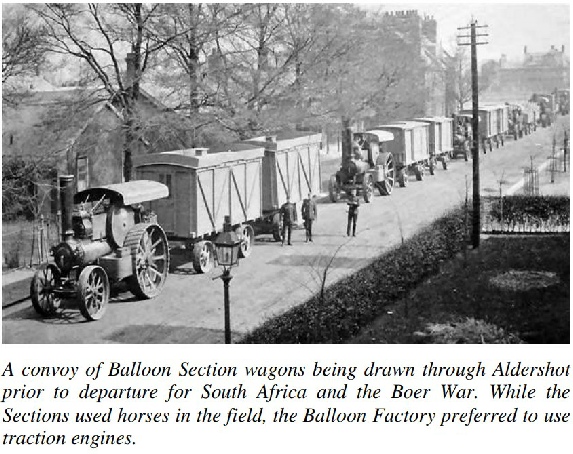

During his time at the Balloon Factory, Templer became an authority on steam traction engines, or Steam Sappers as they were then know by the Army. Before returning from the Soudan in 1887, Templer arranged for a number of ‘redundant’ traction engines that were awaiting return to the UK, to be shipped to the Balloon Depot at Chatham. Here they were kept out of sight until the move to Aldershot took place. Templer then had them made serviceable, ‘acquired’ some more and began demonstrating their usefulness to the Army authorities who, by now, had little interest in traction engines. They soon became a common sight as they pulled heavily laden tube wagons during balloon training, or loads of scrap zinc that could be used for hydrogen generation. A typical demonstration was the use of traction engines during manoeuvres which involved a balloon section and which lasted for several months. Careful planning throughout the exercise period allowed gas to be hauled almost daily from Aldershot to the exercise area, a distance of some 50 miles, with the empty gas tubes being hauled back on the return leg. The demonstrations proved a great success and traction engines became an important element of the Balloon Factory’s work. Templer’s expertise was recognised and during the Second Boer War he was temporarily detached from the Balloon Factory and sent to South Africa as the Director of Steam Road Transport.

A curious incident that occurred this time stemmed from Templer’s practice of collecting scrap material and taking it to the Balloon Factory store. Here it was brought onto the books. It was discovered that some of the scrap metal had been stolen from the factory. The NCO in charge of the store had disappeared and was not seen again. Not for another 15 years that is, when he was recognised amongst a group of Boer prisoners! He had been instructing them in field engineering! He was tried by field court martial and shot the next day.

PHASE 3: 1899-1906

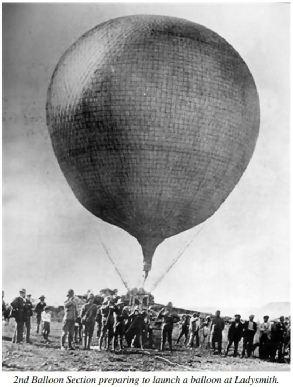

When the 2nd Boer War broke out in September 1899, the Balloon Section and Balloon Factory comprised a mere 4 officers and 40 other ranks. Qualified officers were drafted in and reservists mobilised. By March 1900, 3 sections had been sent to South Africa. A further ‘extemporised’ balloon detachment was later raised as part of the Ladysmith relief force. Balloon depots, complete with mobile gas plants, were set up in Cape Town and Durban. The WO increased the established strength of the Balloon Detachment to 6 sections. In August 1900, a fourth balloon section was dispatched to China to help combat the Boxer Rebellion and a fifth section was sent to Australia.

Throughout the war, the work of the Balloon Factory doubled. Over 30 balloons, plus all associated equipment, were manufactured and sent out to South Africa. In Templer’s absence, Lieutenant Colonel Macdonald acted as Superintendent of the factory. In August 1900 Macdonald was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel F C Trollope and he remained in post until Templer’s return in February 1901.

Following the war, a WO Balloon Committee reviewed in depth the lessons learned about military ballooning. Their final report demonstrated the Army’s growing confidence in balloons and recommended that there should be an established place for them in its future organisation.

The ballooning branch reverted to a peacetime establishment, based on 5 balloon sections (soon re-

3 officers

31 dismounted men

32 mounted men

54 horses

10 wagons

In 1903, Templer handed over as Commandant of the Balloon School to Brevet Major J E Capper although he remained as Superintendent of the Balloon Factory until 1906. Like Templer, Capper (who had assisted in the construction of the “Sapper”) was an energetic, enthusiastic and dynamic figure. He focused on the training and operational work of the Balloon School but he also provided manpower to assist in the experimental programme run by the Balloon Factory. At this time, British ballooning had reached its zenith but both Templer and Capper recognised (particularly after the Wright Brothers flight in December 1903) the growing emergence of dirigibles (airships) and aeroplanes. The WO did not share their foresight so funding was limited. Templer designed a dirigible and built an envelope for it. However, a shortage of funds to purchase an engine, etc, prevented completion of its design and construction.

One success came though Templer’s suggesting to Capper that he should contact Samuel Cody regarding Cody’s ‘war kites’. Capper saw a demonstration of the kites, which used a string of kites to lift an observer over 1,000 feet, and recommended that Cody be hired to construct kites for the Army and act as the chief kiting instructor. Kites could operate in higher winds than standard balloons (up to 50 mph) and could use much of the equipment and drills employed for balloon work. The biggest triumph though was the hiring the enterprising Cody as he went on to build and fly British Army Aeroplane Number 1.

In 1903, a search began for a new home for the Balloon Factory, away from the by now cramped quarters in Aldershot. The need for space to construct an airship was becoming urgent. Eventually a site at Farnborough Common was chosen. The move to the new factory, and its airship shed, was completed in 1905.

Although still only a militia officer, Templer continued to work as head of the Balloon Factory, an RE unit. Some senior officers were very hostile towards him. Some also resented the fact that the Balloon Factory was an independent unit not under control of the surrounding Aldershot Command. An example of this hostility occurred in 1905 when Templer’s chief administrative assistant, Superintending Clerk (warrant officer) John Henry Jolly was court martialled. He had visited a company interested in purchasing oxygen, a by-

During the trial, Templer spoke highly of Jolly’s work, stating:

“ …. He considered him (Jolly), and always should consider him, worthy of every trust …. His signature for the drawing and signing of cheques was always taken …I have represented this to the auditors and no objection was taken ….”

In his evidence, Capper said of Jolly that

“ …. the prisoner was altogether and exceptional man ..… he felt that in the case of this man the confidence reposed in him was fully justified”.

Given the strength of the evidence in Jolly’s favour, French’s rather underhand and indirect attack on Templer is surprising, especially over such a relatively ‘trivial’ crime. Surprising that is except when considering French’s hidden agenda of getting rid of Templer and bringing the Balloon Factory under control of the Aldershot Command.

But Templer’s days were numbered. He had no real opportunity to defend himself against French’s criticisms. French’s letter had the desired effect. Despite 30 years of unsurpassable service and his evident energy and drive, the WO decided to retire him. His 60th birthday on 27 May 1906 was used as the excuse for his dismissal. Command of the Balloon Factory passed to Capper. At Capper’s request though, Templer was re-

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MILITARY BALLOONS

It is, perhaps, at this point that the a description of some of the issues surrounding ballooning should be made in order to understand the nature and importance of the experiments which were carried out and which dictated the course of balloon development over the years.

The objectives of ballooning developments

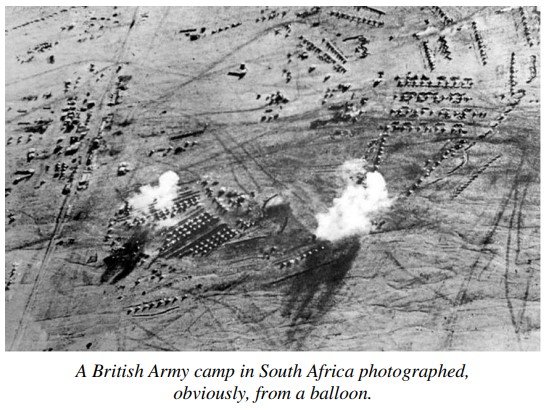

From Templer’s arrival at Chatham until he handed over command of the Balloon Factory in 1906, development of British military ballooning continued unabated. Whilst in charge of the Balloon Factory, he focused primarily on manufacturing. But Templer was always intimately involved in all aspects of ballooning development. His key objective was to make military ballooning ‘fit for purpose’: to transform it from a series of theoretical investigations using borrowed balloons, equipment and soldiers (with limited knowledge of the subject) into a properly equipped, professionally trained force that was a recognised part of the order of battle. Balloon units had to be deployable overseas, able to operate under field conditions. Practical equipment had to be designed and built, often by the RE themselves. Processes had to be devised and practiced for using the equipment. Of particular importance, drills were needed to fill balloons, winch them up to the required operating height, haul them down, and deflate them. Special wagons, based on the standard GS wagon, for carrying gas tubes, balloons, cable and other equipment had to be built. Balloon observers needed their own drills for both tethered ascents and free runs (when the balloon was allowed to drift freely with the winds). Experiments were carried out in aerial photography, meteorology and telephone communication between the balloon and the ground. All of this required an extensive and continuing programme of designing and building equipment, and then working out how it could be used, transported and integrated into the operational balloon sections.

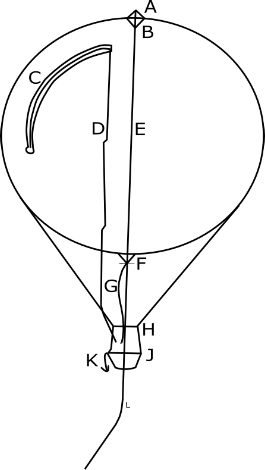

PARTS OF A BALLOON

A. The valve.

B. The valve-

springs.

C. The ripping-

D. Ripping-

E. Valve-

F. Neck.

G. Neck-

H. Hoop.

J. Basket.

K. Grappler.

L. Trail-

By the 1870’s, the basic design of military balloons was fixed although there were variations between the designs adopted by different countries, e.g. the way the basket was attached to the rigging. Minor improvements to the fundamental design were made continually. However, balloon performance was affected by 2 key factors: the gas used to inflate the balloon and the fabric from which a balloon’s envelope was made (this affected the balloon’s ability to retain gas, and maintain lift). These factors, in turn, affected the design of equipment needed to operate and transport balloons, particularly in the field.

Selecting the most suitable gas

At this time, 3 gases were used for inflating balloons:

- Hot air: Although used in the early balloons, hot air was considered to be hazardous and it could only be used for very short periods of time. It was impractical for use by military balloons.

2. Coal gas (town gas): Favoured by sports balloonists, town gas was cheaper than the hydrogen alternative. It provided less lift than hydrogen so that balloons had to be larger and more gas had to be purchased, manufactured, transported and stored. From the military perspective, its use was limited to operations being carried out in developed countries, fairly close to local gas supplies. For a time, British policy was based on the use of coal gas, but it was quickly realised that the planned scenario did not match the type of warfare in which Britain had become engaged i.e. relatively mobile warfare fought in remote counties without a developed infrastructure.

Reports of meteorological flights by Templer and Mr R H Curtis in the coal gas-

“ 8 September 1881-

3. Hydrogen: Hydrogen possessed a superior lifting power over town gas and this characteristic overcame most of town gas’s limitations. However, hydrogen had its own drawbacks. Local supplies were virtually non-

Around 1881, the Army selected hydrogen as the preferred gas for its balloons and soon began experiments aimed at:

- Reducing the cost of its manufacture,

- Improving the quality of hydrogen,

- Developing a portable (mobile) manufacturing plant,

- Developing a practical, ‘lightweight’ method of storing and transporting hydrogen, in support of mobile, field operations.

The manufacture of hydrogen

In 1872, members of the Balloon Sub-

In 1873, a plan to send a balloon detachment, complete with gas plant, with the Ashanti Expedition to West Africa was also scrapped. The plant would have utilised the zinc and sulphuric acid process and would have been broken down into 80-

An important step forward made in the next few years was the decision to transport hydrogen in steel tubes. Various designs were tried and gas manufactured in Chatham was sent out in tubes with the balloon detachments of the Bechuanaland and Soudan expeditions of 1884-

Gas manufacture by the Army became centred on the zinc acid process. However, in 1896, Templer received permission to purchase a small plant to manufacture hydrogen (and oxygen) by the electrolysis of water. The trial was highly successful, with high quality gas being produced at relatively low cost, and the zinc acid process was phased out.

The introduction of Goldbeater’s Skin

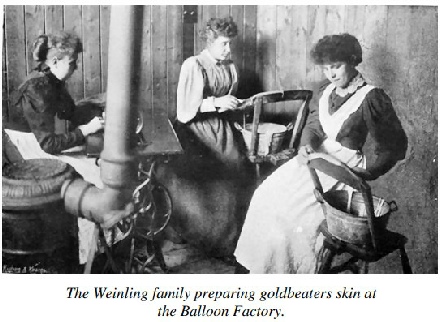

Women in Engineering - The Weinling ladies by Nina Baker

Before Templer was recruited in 1878, a number of fabrics had been used make balloon envelopes, e.g. varnished silk and cambric treated with varnish or linseed oil. To achieve the required inherent strength, multiple fabric layers were used. The main limitation of these fabrics was their porous nature. Their porosity increased as the fabric was exposed to the weather. Inability to retain gas meant that envelopes had to be larger to provide sufficient lift for longer, balloons had to be re-

- The amount of gas needed to inflate the balloons

- The required frequency of refills

- Conditions such as altitude and local temperature which affected lift

The nature of the countryside and infrastructure over which the balloon, gas and their equipment would have to travel

Minimising the overall gas requirement was the key and this was dictated by the choice of fabric used for the balloon’s envelope.

It was Templer who came up with the answer. He had met an Alsatian family, the Weinling’s, who lived in east London. They manufactured small balloons for toys and scientific experiments out of material made from the lower intestines of oxen. The material was lightweight, had great inherent strength and was almost impervious to hydrogen. It was called goldbeater’s skin as it was used in the process of making gold leaf. Templer obtained approval for the Weinling’s to be employed by the Army. In 1883, they worked on the production of a successful new balloon, the “Heron”, the first of many balloons and airships built for the Army over the next 30 years. Goldbeater’s skin remained a secret held only by Britain and gave them a lead over their continental rivals that lasted until the advent of airships.

Goldbeater’s skin was not without its drawbacks. Its cost was very high; it was a price only the military could afford. This eventually led to the development of alternatives such as rubberised cotton. An average size balloon required the intestines from 74,000 oxen that were made into multi-

Manufacturing the Army’s balloons

When, in 1873, Britain was considering deploying balloons on the Ashanti expedition and Henry Coxwell offered to provide two for princely sum of £2,000. 5 years later, when Templer was appointed to assist the Balloon Sub-

Goldbeaters’ skin was introduced in 1883. Gradually, standard classes of balloon were developed. Classes varied in size from 5,000 to 14,000 cu ft; each intended for use under different conditions, e.g. temperature, humidity, operating height above sea level, number of observers, etc. Balloons were manufactured by the Balloon Factory (and its predecessors) by a mix of RE tradesmen and civilians (including the Weinling family). The Factory was also responsible for the design and repair of balloons.

Balloon secrets – an unexpected drama

In 1888, a shocked, balloon world learnt of the arrest and court martial of Major Templer. As a result of evidence provided by Templer’s boss, Major Elsdale, 8 charges were laid against him. A general court martial began on 5 April and lasted for 4 days. Templer was accused of scandalous conduct by lying about visits to a civilian balloon manufacturer in Birmingham, and of passing balloon secrets to a foreign power, Italy. Messrs Howard Lane and Co had manufactured a balloon for the Italian army. Its design was very similar to those used by the British Army, as were its goldbeaters-

The prosecution’s case began falling apart once defence witnesses proved that Templer was with them when he was accused of being in Birmingham. Even Elsdale agreed that he was with Templer on one of the days in question. He had never been to Birmingham on any of the days in question! The trial was stopped and Templer was acquitted. “The Times” reported:

“Major Templer was warmly congratulated by a number of officers, and on leaving the Court-

The court martial was the subject of parliamentary questions. The Secretary of State for War (E Stanhope) stated:

“The result of the Court Martial has absolutely cleared Major Templer from the slightest suspicion of any sort or kind. I have seen Major Templer, and expressed to him my satisfaction that he should have so completely vindicated his character”.

Major Elsdale was posted.

THE BALLOONS GO TO WAR

Bechuanaland and the Soudan (1884-

In 1884 a balloon detachment was prepared for dispatch up the Nile as part of the Soudan campaign. The best of the available balloons and equipment and the majority of trained manpower were selected for the expedition. In the event, the detachment under Major Elsdale was sent instead to Bechuanaland as part of an expedition to combat the Boers in Western Transvaal. It comprised 2 officers and 10 NCO’s and sappers. Three skin-

Following the fall of Khartoum in 1885, an expeditionary force, which included a balloon detachment, was sent to Suakin. Equipping the detachment was a problem as most of the available men and equipment were in South Africa. Three smaller balloons “Sapper”, “Scout “ and “Fly” were sent out to the Soudan, along with 22,000 cu ft of hydrogen in tubes and a small gas production plant. Only 2 officers, Major Templer and Lieutenant R J H L Mackenzie, and 8 NCO’s and sappers were available. Untrained soldiers were borrowed from other units to bring the detachment up to strength. A number of ascents were made. Lieutenant Mackenzie (relieved by Sapper Wright at noon) successfully observed from a balloon towed by a wagon at a height of 200-

“On 25th March, when the balloon was able to accompany the convoy, the men derived the greatest confidence from it as they knew they could not be surprised, and the convoy itself could move much faster and more freely, halting only occasionally to close up. The subject, however, is of such vast importance that it is hoped that the experience gained in this campaign may be utilized and the science still further developed, when it cannot fail to be of the greatest advantage of an army in the field, especially when operating in broken country, or when covered in thick bush like the neighbourhood of Suakin.”

Both detachments demonstrated that they were too small to properly carry out their allotted tasks. The Suakin detachment was unable to use their portable gas plant because no trained men were available to operate it. The shortage of trained balloonists and absence of the their own horses and drivers added to the problems. In his report, Colonel J Bevan Edwards commented on the difficulties:

“The detachment employed was numerically too weak for the duty, and it is absolutely necessary that the men should be trained and drilled in handling the balloon in a moderate breeze. On the 2nd April we were obliged to supplement the detachment with men from the Royal Engineer companies, who had never worked a balloon before, consequently they were quite unable to keep it steady.”

South Africa (1899-

4 balloon sections served during the South African War. At the outbreak of war in 1899, only one section existed but it was quickly decided that a second section should also be deployed. Sufficient stores were available and manpower was found by mobilising trained reservists and training additional men. Gas production plants and balloon depots were set up in Cape Town and Durban.

a. 1st Balloon Section

1st Section, commanded by Captain H B Jones, departed for South Africa on 4 November. They were sent to the left flank of the British advance and attached to Lord Methuen’s division. Conditions for flying were often unsatisfactory but ballooning continued none the less. Successful aerial observation was carried out at the battle of Magersfontein, and during the march on Paardeberg. A successful attack was then made on Cronje’s laager, when the section, using the Balloon “Elsie”, began spotting for the British artillery that had been firing blind. The “Duchess of Connaught” was hit and brought down leaking badly.

During the advance to Bloemfontein, the section was attached to the cavalry division. As the cavalry advanced along the Modder River, a balloon spotted hidden Boer artillery. Support was then given to the Naval Brigade’s guns and the way to Bloemfontein was soon cleared. Finally 1st Balloon Section was attached to 11th Division during the advance towards Pretoria. Balloon support was provided at Vet River and Zand River. After the fall of the Boer capital, it was intended that the section should support operations in eastern Transvaal. However, a shortage of oxen (used to tow both heavy balloon wagons and artillery pieces) meant that the balloon section was without transport. It was, therefore, broken up and its men transferred to other units.

b. 2nd Balloon Section

Commanded by Major G M Heath, 2nd Section embarked on 30 September for Natal. They reached Ladysmith on 27 October, without all their stores. They were immediately trapped inside the besieged town. Just 3 days later, they were in action, during the battle of Lombards Kop. For the 27 days that hydrogen stocks lasted, the section continually observed Boer movements. The section spotted for artillery, especially the Naval Long Toms, produced sketched maps of Boer positions and located enemy artillery. The Boers concentrated artillery fire on the balloons, bringing a number down. As predicted by the experiments at Lydd, damage to the balloons was slight and they were soon repaired. After the hydrogen was finished, the section was employed as field engineers. Following the relief of Ladysmith on 28 February 1900, they were converted into a mounted engineer unit, 3rd Field Troop RE, and served with the cavalry.

c. 3rd Balloon Section

This section arrived in Cape Town in March 1900. It was commanded by Lieutenant (temporary Maj) R B D Blakeney and was attached to 10th Division on Lord Roberts left flank. Initially the force was assigned to the relief of Mafeking. When the balloon “Trumpet” was emptied on 9 May, the section had been in action continually for 15 days. Mafeking was relieved shortly afterwards. The section’s most noteworthy achievement was the action at Fourteen Streams where the Boers were forced to evacuate the right bank of the Vaal. Balloon observers had located the Boers’ positions and began to watch their movements. They then successfully started directing the fire of the British guns. These included a railway-

d. Extemporized Balloon Detachment

When 2nd Balloon Section was trapped inside Ladysmith, its reserve stores were left behind at Pietermaritzburg. A balloon detachment, commanded by Captain G E Philips was extemporized from these reserves. The detachment was always handicapped by a shortage of trained men and equipment and by the cumbrous nature of its ox transport. However it was able to spot for artillery at Spion Kop, at the final crossing of the Tugela River and during the shelling of Boer trenches at Pieter’s Hill. After the relief of Ladysmith the detachment was disbanded.

e. British balloons from a Boer viewpoint

In March 1904, Arthur Lynch MP, a former colonel in the Boer Army gave a lecture in Paris on the role of “English” balloons in South Africa. It would be true to say that the Boers disliked the balloons intensely. He reported that balloons were a great asset to British troops, especially at Ladysmith, Colenso, the Modder River and Fourteen Streams. He remarked:

“…. observation made by the help of a balloon often permitted the English to note exactly the position of a battery, of a laager, or of military works. Therefore, the Boers took a dislike to the balloons. …. The balloons were a symbol of superiority on the side of the English which seriously disquieted them. …. They (the British) were so well informed about the Boer positions that they could divine the object of a combined movement and …. repulsed the attack on Platrand or Cerai’s Camp ….”

“To sum up my observations, I believe that the balloon is of the greatest value in military operations, above all in sieges, and in that instance as much to the besieged as the besieger.”

f. Lessons learned in South Africa

The balloon establishment had proved it was able to form, equip and deploy (and then support) three balloon sections to South Africa, support the extemporized balloon detachment and also send Number 4 Balloon Section to China and Number 5 Balloon Section to Australia. All of this in the space of a year! It demonstrated the progress that had been made since Grover’s report in 1862 and Templer arrival at Woolwich in 1878. Both the balloons and equipment worked well, the sections’ establishment was about right and the skills of the soldiers were a credit to the training regime. The lack of draught horses, and later of oxen, in South Africa was a great handicap. Although the balloons were of particular benefit during siege operations, they were not used during the guerrilla warfare stage of the war where targets were both small and fleeting. The war did again demonstrated one particular weakness of balloons. They could not be operated in winds of above 25 m.p.h. The main problem was the total lack of stability in the basket that could swing violently across the skies. Balloonists became very sick and they lacked a stable platform from which to make observations. It was this limitation that Cody’s war kites were designed to partially overcome.

The war also demonstrated the other inherent weakness of balloons, particularly free running balloons: their lack of manoeuvrability. To be able to see beyond the next hill and then return with the information was the wish of every commander. In a talk to the Royal United Service Institution Templer once described how he had criss-

After the war, training moved further forward. Particular attention was paid to artillery cooperation at practice camps. Balloon sections participated in more manoeuvres and exercises. Some phases of the South African war showed a need for mobility on the part of all participants so particular attention was afterwards paid to getting balloons into action and hauling them down again. To improve the control of indirect artillery fire, telephone communications between a balloon and the ground was made more reliable.

China

In August 1900, the 4th Balloon Section under Lieutenant Colonel J R L Macdonald embarked for China. On arrival, he was replaced by Captain A H B Hume. The well-

Conclusion

When Templer joined the Balloon Department in 1878, British Army ballooning was in its infancy. When he left in 1908, balloons were an accepted feature of both peacetime and wartime military deployments. Ballooning’s development had overcome many and varied obstacles: technical, personal, financial and political. Resistance to change had been defeated. By 1908, ballooning was well established yet battles were still being fought -

Templer was not solely responsible balloon development; many other officers had also participated in the work. What made Templer different from everybody else was the continuity of service that his commission as a militia officer allowed. Regular soldiers were posted away after 2 or 3 years. Only a few such a Major C M Watson returned for a second tour with the balloons. Templer served continually for 30 years. His long service was coupled with a strong and determined personality.

Obstacles would not deter Templer; he had boundless energy and knew whom to go to get what he wanted. Professional soldiers were more deterred by the niceties of the chain of command. Templer could afford not to be. Major General Capper said of him:

“He was not always popular with his official superiors as his disregard of regulations and impatience with official delays and restrictions which stood in the way of frequently led to conflicts with them, but in the end he generally managed to get his way and convince them he was right.

His wonderful enthusiasm, his kindly temperament and dogged determination to push things through in the face of every obstacle, and his refusal to be downcast over any set-

Templer’s had an inventive, scientific turn of mind and was ideally suited to the experimental and manufacturing environment in which he worked. He possessed a strong sense of duty and this kept driving him forward. For these reasons, Templer’s contribution to the development of military ballooning for the British Army sets him head and shoulders above his contemporaries. He can, therefore, justifiably be called the “Father of British military aviation”.

End Notes and Bibliography

1 “Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers”,

New Series Volume XII 1863:

Paper X “On the Uses of Balloons in Military Operations” Lieutenant G E Grover RE

Paper XI “On Reconnoitring Balloons” Lieutenant G E Grover RE

Paper XII “On Balloon Reconnaissance as Practised in the American Army” Captain F Beaumont, RE

2 Ibid, Paper XI, page 103

3 Ibid, Page XII, page 93

4 “Professional Papers of the Corps of Royal Engineers”, Volume XXVIII, 1903

Paper III “Military Ballooning in the British Army” Colonel C M Watson

WO 32/8584, pages 11-

“The Times” 13 December 1881

Air 1/728/176/3

WO 32/6068, report “War Balloons”, dated 10 June 1886

“Professional Papers of the Corps of Royal Engineers”, Volume XXVIII, 1903

Paper III “Military Ballooning in the British Army” Colonel C M Watson

“Flight”, page 376, 26 June 1909

“Reminiscences of Colonel J L B Templer” Brigadier General R D B Blakeney

“More Reminiscences of an Old Bohemian” Major Fitzroy Gardner

WO 32/6068

“Final Report of the Committee on Military Ballooning” 1904

“Early Aviation at Farnborough – Balloons Kites and Airships” Percy B Walker, pages 78-

National Army Museum NAM-

RUSI “Journal”, page 261 Volume 36 (1892)

“Military Ballooning” Lieutenant H B Jones RE

“Professional Papers of the Corps of Royal Engineers”, Volume XXVIII, 1903

Paper III “Military Ballooning in the British Army” Colonel C M Watson

RUSI “Journal”, page 262 Volume 36 (1892)

“Military Ballooning” Lieutenant H B Jones RE

“The Early History of British Aeronautics” Brigadier P W L Broke-

“Daily Mail” 9 March 1900

“The Early History of British Aeronautics” Brigadier P W L Broke-

“The Times” 6-

“Hansard”, 19 April 1888, Volume 324 cc1724-

WO 32/6134

“Report on Royal Engineers at Suakin” 1885

“The Early History of British Aeronautics” Brigadier P W L Broke-

The Military Historical Society “Bulletin”, pages 5-

“History of the Corps of Royal Engineers”, pages 278-

Air 1/728/176/3/8

RUSI “Journal”, pages 137-

“Military Ballooning” Captain J Templer Royal Middlesex Rifles

WO 32/6059

“China, 1900-

“The Journal of the Royal Engineers”, Volume XXXVII 1924, pages 142-

The above is an unabridged version that was sent to me by Michael Dunn before it was published in the RAF Historical Society Journal 55 -

To close any picture press Alt + Left Arrow