The loss of the Halsewell

and Charles Beckford Templer(1770-1786)

The Halsewell was a grand East Indiaman merchant ship. It had a rich cargo and the passengers included the Captain's two daughters and nieces. Thomas Burston, the First Mate, was also related to the Captain. It was to have been Captain Pierce's final voyage before he retired.

The ship was sailing to India to trade. In January 1786, as it headed west down the Channel, a terrible storm developed. For several days the ship fought against blizzards and hurricane force winds until finally it was driven onto the rocks at Seacombe, near Worth Matravers.

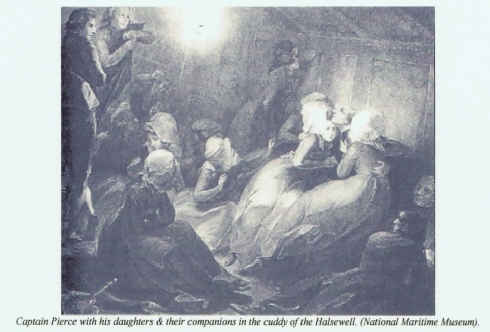

More than 380 people lost their lives including the Captain's daughters and nieces. Captain Pierce and his nephew, Thomas Burston, could have saved themselves but chose instead to comfort the young women as best they could and drowned with them

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

On 1st January 1786 the Halsewell, a fine East Indiaman of 777 tons, left the Downs on the start of its third voyage to Bengal under the command of Captain Richard Pierce, one of the most senior captains in the Company. Already he had made what was then described as 'a competent fortune' and it was his avowed intention that this trip would be his last, as he planned to retire to his large estate at Kingston in Surrey and enjoy the abundant wealth that his 25 years in the East India Company's service had brought him.

On this particular voyage there were eight passengers on board, a relatively small number for a Company ship - one gentleman and seven young ladies - of which two were the Captain's own daughters. Amongst the crew were seven midshipmen and five supemumaries - young lads of about twelve years taking their first steps towards a prosperous career in the very coveted Company. With the addition of an unknown number of troops going to serve in the various East India garrisons the total number on board the vessel was reportedly over 400 persons.

One of those on board was Charles Beckford Templer, the youngest son of James Templer Esquire of Stover Lodge in Devon. Fourteen year old Charles had left Westminster School six months previously and was en route to Bengal to begin a career with the East India Company. No doubt he was carrying letters of introduction from his Uncle George Templer Esquire of Shapwick, Somerset, who himself had returned from Calcutta only a year earlier, with a competent fortune of his own, earned in Calcutta after all year career there with the Company.

The second day out in the Channel found the vessel becalmed off Dunnose Head, the most southerly point of the Isle of Wight, but this was just the lull before the storm. By the evening the wind had freshened with more than a hint of snow in the air. The next day saw a strong gale blow from the north-east, so that the Halsewell made quite extraordinary speed down the Channel but at the same time shipping a fair amount of water. By late evening the glass had dropped alarmingly and during the night the strengthening wind had veered to the south. It was then realised that some damage had been sustained by the vessel. It had sprung a leak and the crew were set to work at the pumps.

On the 4th day the vessel now had at least seven feet of water in the holds, it was rolling most dangerously and the situation appeared serious. Captain Pierce ordered that the mizen (third after) mast be cut down to lighten the vessel, and a few hours later the main mast was also cut away. In the process five seamen were carried overboard in the mass of rigging; their bodies were never recovered. Certainly nothing was going right for Captain Pierce on his last trip. By mid-morning Berry Head was sighted, this is the most southerly point of Torbay and as the weather had eased somewhat the captain decided to turn back and bear away for Portsmouth. With some blessed relief from the elements he ordered jury masts (a temporary makeshift rig) and as much canvas as could be safely carried in the conditions. There seemed no doubt in Captain Pierce's mind that the vessel could safely make Portsmouth.

But after a day of slow and painful progress in worsening weather Portland Bill was sighted to the north-east. The Captain knew that he could not make for the shelter of Portland Roads so he attempted to guide the vessel to Studland Bay. Now the Halsewell was at the mercy of the tides and the howling gale. Just before midnight St Aldhelm's Head was sighted about a mile and a half to the leeward. All sail was reduced and a small anchor was released, but in less than an hour this failed to hold the vessel. The sheet anchor was dropped which again failed to stop the vessel as it was being driven towards the rocky shore.

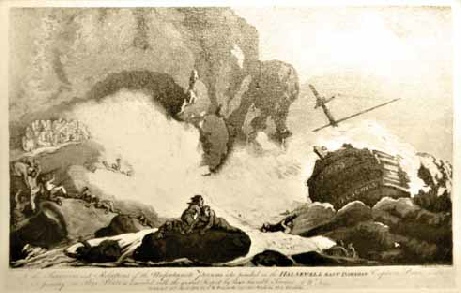

About two in the morning of 6th the Halsewell struck the rocks just below Winspit near Seacombe. A more inhospitable spot could not have been found - formidable cliffs almost rising perpendicular from the rock-strewn seas. The vessel went on to the rocks with 'such violence as to dash the heads of those who were standing in the cuddy [a small cabin at the aft usually reserved for the Captain and passengers] against the deck above them...A shriek of horror burst at one instant from every quarter of the ship...' Utter terror had struck the passengers as the vessel creaked and groaned as it was ground upon the rocks before turning broadside to the cliffs. The Halsewell was effectively lying in the mouth of a large cavern hollowed out of the cliffs, making it completely invisible to any person on the cliffs high above if indeed anybody was about on such a night!

Several reports suggest that the crew refused to obey orders and were only concerned in making their own escape from the doomed vessel. Mr Meriton, the second mate, was amongst the first to get ashore on to the rocks in an attempt to raise the alarm but even in the pitch darkness he quickly realised that the sheer cliff-face seemed unassailable. Other members of the crew had managed to escape, crowding on to the rocks and the floor of the cavern, which was continually flooded by heavy waves. Shortly before dawn, just as two officers were washed off the vessel, making the comparative safety of the rocks with the greatest of difficulty, with a final horrendous crash 'She [Halsewell] disappeared into a terrible cavern'.

Many of those that had escaped from the vessel did not survive until morning, some had been dragged off the rocks by the force of the sea and others died from cold and fatigue. Then, with the coming of the morning two brave men - the cook and the quartermaster - managed with great skill to climb the cliff face. They staggered to the nearest house, the home of a Mr Garland, who was the steward of a nearby quarry. He quickly gathered together a party of quarrymen well acquainted with the cliffs and very experienced with ropes and stakes. Ropes were dropped over the cliff into the mouth of the cavern and slowly and perilously the survivors were hauled to safety; some were so numb with cold that they experienced problems just tying the ropes around their bodies. One report suggests that the intrepid rescue lasted for almost 24 hours. One of the last persons to be rescued was Meriton, the second mate, who later wrote about the wrecking and the rescue. In total 74 persons were rescued by these methods although it was thought that almost the same number had escaped from the vessel but had died during the night. The death toll of the Halsewell was put at approximately 386 persons - a terrible shipping tragedy.

The Captain Richard Pierce, his two daughters Miss Eliza Pierce, Miss Mary Anne Pierce, his two nieces, Miss Amy Paul, Miss Mary Paul, the daughters of Mr Henry Paul and Capt Richard’ sister Ann Piece, together with the young Charles Beckford Templer, all perished. Jane Paul who had married George Templer HEIC in 1781 was the sister to Amy and Mary.

The financial loss of the vessel was estimated by the East India Company to be in the region of £50,000. In recognition of the brave and daring rescues by the quarrymen, the Company awarded them with 100 guineas to share amongst themselves; later their quarry was renamed the Halsewell. There was quite an outcry in the press when it was known that seven young ladies had died in the wreck. Several reports condemned the whole concept of taking young girls over to India to be paraded in what they called 'the marriage market for East India Company moguls'! Also there was a rather dramatic account of the shipwreck in the Annual Register, which is said to have so impressed Charles Dickens that he used it as a basis for his story The Long Journey. Other than the folk memories of this 'Great Shipwreck' as it was called by some Victorians, a few items from the Halsewell have survived; one of which is an hour-glass that runs for four hours. Washed ashore with the green glass intact, it is now housed in the Dorset County Museum.

Near the site of the wreck on the cliffs above there are still traces of four long graves, though it is not known how many bodies they contain. The nearby church of Worth Matravers records only one burial from the Halsewell, that of a body washed ashore almost one month later. The vicar recorded in his Parish Register, 'On 4, 5, 6 Jan - a remarkable snow storm sometimes a hurricane with the wind at south, on the latter day Halsewell - Never did happen so complete a wreck. The ship long before day break was shattered to pieces and very small part of the cargo survived.'

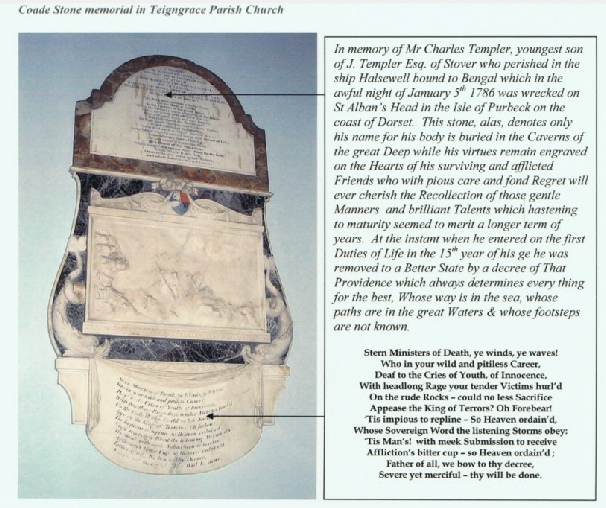

One can only imagine the anguish of families who lost loved ones in this dreadful tragedy. Charles Templer had been the youngest of the seven surviving children of James and Mary Templer, although both of his parents had died within the past four years and were spared the agony of the loss of their youngest son. So it was on his elder siblings that the burden of his loss fell most heavily. His three elder brothers, (James, John and George) had already embarked on the demolition and reconstruction of the local parish church at Teigngrace, in conjunction with their sister Anne and brother in law, Sir John William de la Pole of Shute in East Devon to commemorate their parents. It was appropriate that they incorporated a memorial in Coade Stone in the new church to commemorate their young brother. Sir John William de la Pole also placed another memorial at the Shute Church, which read as follows:

“Sacred to the memory of Charles Beckford Templer who on the night of January 6th 1786 perished in the Halsewell, East Indiaman in Studland Bay. This monument in testimony of mutual regard between the unhappy victim and his tributary friend and brother is erected by Sir John W. Pole 13 October Ob Aet 16“

Charles Templer’s brother, John, was the first Rector of the new church, remaining as incumbent for 45 years. The opening of the new church took place on Sunday, March 30th 1788, just over two years after the Halsewell tragedy.

The loss of the Halsewell created a sensation at the time, akin to the loss of the Titanic in 1912. It formed the subject of numerous poems and paintings by famous artists, including James Northcote R.A.. It is probably unique among famous shipwrecks of the day in having been chosen as the subject for a “grand instrumental piece” entitled “The Shipwreck, or loss of the Halsewell East Indianman” by A.F.C. Kollmann. Organist of His Majesty’s Chapel at St James’, which was published in London in 1796. Kollmann was bom near Hanover in 1756 and came to England in 1784 as schoolmaster and organist at the German Chapel in St James’. To him is really due the credit of first making any of Bach’s music available in this country.

Notes:

Halsewell: 776.90/94 bm. 112’3 x36’l x 15’1

24.8.1778: Launched by Adams & Barnard, Greenland Dock, for Thomas Burston.

Laid down as Earl of Ashbumham but renamed before launch. Captain Richard Pierce.

a) 7.3.1779-20.10.1781: Voyage to the Coromandel Coast and China;

b) 11.3.1783-28.8.1784: Voyage to the Coromandel Coast and Bengal;

c) 1.1.1786 Began Voyage to the Coromandel Coast and Bengal;

d) 6.1.1786- Wrecked on the rock later known as Hasewell Rock, Peverill Point, west of Swanage after her cables broke while sheltering in a heavy gale and snowstorm.

Sources:

■ Ships of the East India Company, by Rowan Hackman & the World Ship Society, 2001; ISBN 0 905617 96 7

■ Pamphlet for refurbishment of the organ at Teigngrace Church 1960 With reprint of article from Mid Devon Advertiser,

19 November 1960.

Edited by SJDrabble with reference to Charles Templer

April 2007

Halswell Book

Halswell Book

Coade Stone

Coade Stone